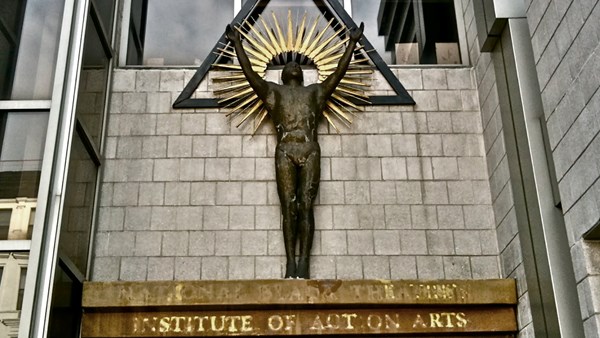

Metro Hope Church rents space from Harlem’s historic National Black Theater. We’re located just off 125th Street, Harlem’s main corridor. On Sundays, this little corner of Harlem can feel like a religious food court experience. We share space with other churches … and cults—the church of Scientology meeting adjacent to us. We “fight” for signage space while churches display their wares for tourists seeking a true Harlem experience. We’re like information booths for purveyors of gospel choirs and smothered chicken.

On any given Sunday you might hear me say, “Welcome to Metro. We’re grateful you made us your stop today. If you feel your experience is lacking here, you can head on over to Mount Moriah Church—they have a gospel choir just across the hall—but just remember, they won’t serve you glazed donuts with fair trade coffee …”

Well if I don’t say it, I’m thinking it.

But despite my occasional cynicism, I’m convinced Metro’s presence and staying power is vital to our community. What was once a great adventure in “What’s the point of another church in Harlem?” has rooted and defined our distinctive reach into the very arteries of our community. It has been a slow, long journey in a city where only the most resourced survive. Yet in working in a rapidly changing context like East Harlem, we position ourselves in a posture of prayer and discernment, seeking clues about the gifts others bring. We are open to God working through others to shape our collective vision and vocation, acknowledging how every person brings gifts that can further God’s enterprise in the world.

The Rule of the Household

When churches help people reimagine how their gifts fit into God’s greater economy, they reclaim a historical role for the church—a role both the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Church have affirmed over the centuries, where the principle of economy is rendered in deeper and broader light.

While the term economy might conjure images of capitalism, NASDAQ, or even a bronze bull on a Wall Street sidewalk, the Greek word oikonomia, from which economy is derived, retains more robust significance and meaning. Oikonomia is defined as “the rule of the household.” It also refers to the responsibility given to humans in creation for managing the resources of the earth (Gen. 1:26).

In God’s “rule of the household,” the church views its gifts and possessions as extensions of this household. People of Christ exercise their distinctive gifts within God’s larger impetus for flourishing in the world.

At home we encourage our son to be a part of the oikonomia as a contributing member. Our daily practices involve love for neighbor, generosity, and hospitality for God’s household translated into our zip code in Harlem. These gifts come in even the simple act of clearing the kitchen table on Taco Tuesday, or the way his artwork graces the front door greeting our neighbors and visitors.

If Christians realized they were an extension of God’s greater household in the world it would make a positive impact. Unfortunately, when many Christians move into a place it’s a form of mindless living in the city, unconscious about the economic disparities and hardships of the surrounding neighborhood. The intention behind moving into a neighborhood can be for the simple reason that it is “up and coming,” superseding any sense of awareness of neighborhood pain and suffering.

The recent boom in church plants in NYC has skewed toward middle-class models that favor the gentry and the elite in formerly working class or middle class neighborhoods. People bring in particular tastes, often overlooking the history and the particularity of long-established businesses, where market forces often favor the up and coming sensibilities. I’ve seen how our panaderias (local bakeries) have been making lattes (café con leche) for years, yet lack the local support of new tenants in the hood.

My wife and I have encouraged our church community to take mindful walks through their neighborhoods. Walking with Mayra, I find she will often stop at two or three businesses at a time, talking to local business owners like Maria, the young Mexican woman selling mango slices at the corner of 116th street. Then we stop by the new cupcake place catering to Harlem’s gentrifying palate. Mayra will take a menu, inquiring about how long they’ve been in business, promising to send people their way.

Within a three-mile radius in Harlem we personally know at least 20 business owners. This is no accident. We encourage our church to see local business support as a form of discipleship—a way of being present in neighborhoods with deep intention.

Keep the Gift Moving

Dollars used locally circulate in communities up to three times longer. Owners can then purchase from local suppliers, who pay local employees, who can then make purchases at the local market … and the gifts move on.

To contribute to economic flourishing is to “keep the gift moving,” an insight from indigenous tribal wisdom. If our gifts stop, and we hoard (think Zacchaeus), or consistently reappropriate (shop elsewhere), imbalances will naturally occur. Notwithstanding, when middle- and upper-class people in poor neighborhoods support local business owners, local economies could function a lot differently.

In support of this idea NPR reported a study done by Network Science. The Researchers tracked the shopping habits of 150,000 people in two major cities. Researchers concluded that if 5 percent of these consumers changed their shopping habits, a noticeable economic change could be seen in neighborhoods with fewer resources. The study states, “The addition of small changes in the shopping destinations of individuals can dramatically impact the spatial distribution of money flows in the city, and the frequency of encounters between residents of different neighborhoods.”

What if churches supported these changes by encouraging not only parishioners but also neighborhood residents to buy local? This could have a quantifiable impact on a whole neighborhood economy. Yet there are even small steps churches can make to witness change on a local level.

As part of a sustained investment, our church supported the East Harlem Café. Our community and arts coordinator, Chantilly Mers, assisted Michelle, the café owner, in raising $10,000 through an online campaign. The money went toward the purchase of a new refrigerator to provide customers with healthier eating options during a time when East Harlem was considered a food desert.

Meanwhile in continuing to sustain our engagement with East Harlem small businesses, our church also organizes monthly “cash mobs,” mobilizing a group of community people to support local restaurants. Our first ever was at the East Harlem Café during a winter storm. Two of our church members volunteered as café servers to accommodate the crowd. Metro’s worship band became the house band for the day. Our church and local residents packed out the café on one of the snowiest days of the year. People from our local community board and local organizations were represented; it was successful particularly during a long winter season with a low revenue tide. According to Michelle, the effort even assisted the café in meeting payroll for the week.

We held another cash mob at a local apparel store named Harlem Underground Clothing Company. The Sunday prior to the event our church hosted the establishment owner. Charlene had the opportunity to share her vision behind the clothing store, which has been in existence since 1998 on Harlem’s busiest corridor, a now-gentrifying shopping strip. The next Sunday a group from our church would shop at the establishment after the service. We also invited neighborhood residents to attend. Charlene reported that through our collective efforts the store earned three times the revenue it had ever made on any given Sunday, an economic boost for a clothing store competing with big box stores less than a block away.

I pondered afterwards, What would happen if there were a movement of churches in Harlem supporting locally owned businesses in our community? How would the neighborhood retain some of its local character, while the hopes and dreams, even the personal economic vitality, of a neighborhood shop owner become a priority to the church?

Not two weeks after our efforts, our church treasurer reported that Harlem Underground Clothing Store tithed back to our church. While this was never presented as a requirement for our patronage, it was the embodiment of the ethic that the gift (our resources) must keep moving. This is how neighborhood ecologies thrive and function, and what signs of economic shalom can look like in our local neighborhoods.

José Humphreys is a facilitator and pastor of Metro Hope Covenant Church, a multiethnic church movement in New York City.

Taken from Seeing Jesus in East Harlem by Jose Humphreys. ©2018 by Jose Humphreys. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove IL 60515-1426. www.ivpress.com

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month