Genesis 1 tells us that God formed the beauties of creation simply because he enjoys them. He made a beautiful world, and then he made people who can appreciate and contribute to that beauty.

Even a cursory glance at any historical period shows us that artistry plays a central role in developing culture and sustaining healthy, thriving communities. In the 6th century BC, when King Nebuchadnezzar captured the Israelites and set about dismantling the nation, he not only exiled the military, he also made sure to destroy the artists and craftsmen (2 Kings 24).

He knew that if he wanted to conquer Jerusalem, he would not only have to overcome the military force, but also those who were responsible for establishing the heart and soul of the culture, the makers.

The formation of creative community has encountered a different kind of adversary in the West. The Industrial Revolution mechanized and streamlined production for the sake of simple uniformity; the focus on efficiency and profit drove craftsmanship into the shadows. Creativity was mortgaged to save margins, and the flourishes and personal qualities of gifted artisans were left to fend for themselves in a harsh economic arena.

Unfortunately, the local church has not been immune to this focus on efficiency. The rise of the industrialized megachurch—with millions of dollars raised for the sake of comfortable and symmetrical square buildings—along with the gradual disappearance of the local congregation, meant that the exquisite neighborhood chapels built long ago by talented, local artisans now sit empty or are appreciated as private residences or amazing cafes.

The modern evangelical church streamlines its expenses when it comes to its physical buildings, giving only fleeting thought to the role of awe and wonder, which are often considered superfluous and excessive. Why have a beautiful sanctuary when a Family Life Center and gymnasium will do? Our places of worship have become indistinguishable from shopping malls, the bland and mundane providing function but lacking inspiration, leaving our latent desire for beauty and transcendence unaddressed in our congregational life.

And yet, the impulse to make sprouts up everywhere, even in a society that deprives it of oxygen and opportunity. Creative desire is, at its core, more than a mere personality trait or interest—it’s a fundamental component of who we are, as creations made in the image of God.

Genesis opens with God creating the heavens and the earth, but it goes on to reveal these creative mandates for Adam and beyond, both in the flora and fauna of the garden, as well as in the building of a place that hosts the very presence of God. God created light—fiat lux—but also created individual humans to be illuminators in their own right.

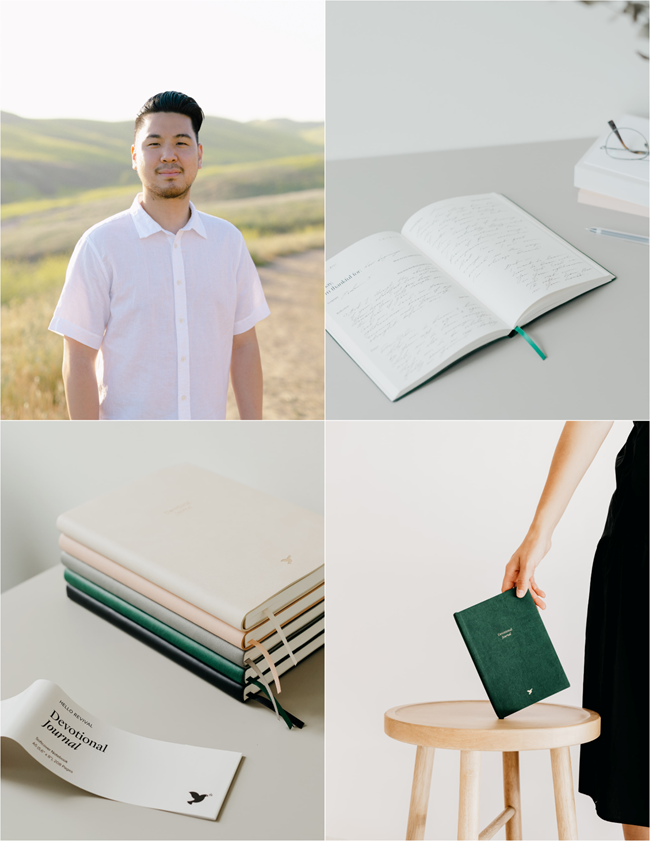

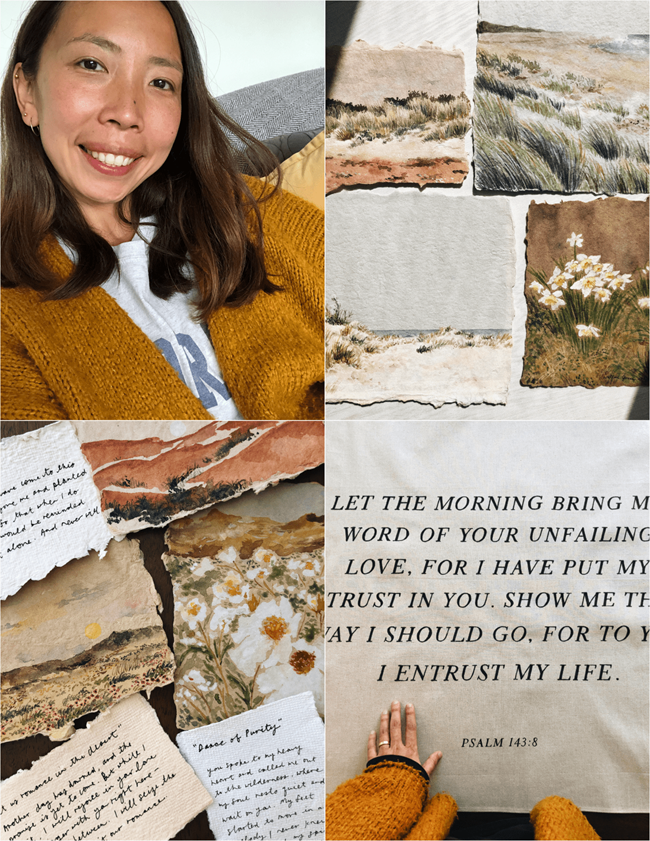

We are most engaged in God’s creation when we ourselves create and when we take joy in the beautiful work of others. And so, we invite you to meet ten makers whose artistry and intention draw us to delight in God and his world.