Among its neighbors, Singapore is a spiritual anomaly. Surrounded by deeply religious countries with overwhelming Muslim or Buddhist majorities, the island city-state is by some measures the world’s most religiously diverse society, with no single faith composing a majority.

Today, two out of three Singaporeans don’t see religion as very important. Yet the country has the region’s highest rate of conversions—including to Christianity—according to a special Pew Research Center study on religion in South and Southeast Asia released today.

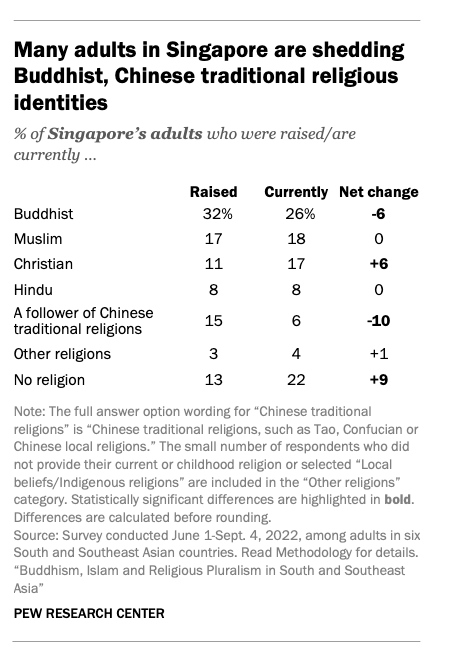

Singapore’s lack of a single dominant religion coincides with more “religious switching,” Pew’s terminology for adults converting to a different religion from the one they were raised in. The percentage of Singaporeans who say they are Buddhists or followers of Chinese traditional religions has dropped, while those claiming to be Christians or religiously unaffiliated have risen.

By contrast, in the five neighboring nations included in the study—Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, and Sri Lanka—nearly all adults surveyed said they continue to identify with the religion in which they were raised. And large majorities consider religion very important in their lives.

For Pew’s latest international report, “Buddhism, Islam and Religious Pluralism in South and Southeast Asia,” researchers surveyed more than 13,000 adults from June to September 2022. The six countries Pew selected are representative of religion in the region: Three are majority Buddhist (Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand); two are majority Muslim (Malaysia and Indonesia); and one is religiously diverse (Singapore).

(Researchers explained that though Sri Lanka is typically grouped with South Asia, the island nation was included because of its ties to Southeast Asia. For example, Buddhists in Sri Lanka predominantly follow the Theravada tradition like in the other majority-Buddhist countries in the study. In addition, while Laos and Myanmar are also neighboring Southeast Asian nations with Theravada Buddhist majorities, their political realities prevented reliable surveying on religious topics.)

The report covers topics ranging from how religion is tied to national identity, the role of religion in government, the attitudes people in South and Southeast Asia have toward other religions, as well as cross-religious practices.

When religion is more than a religion

With the exception of Singapore, all the countries surveyed are highly religious: Nearly all respondents across five nations identified with a religious group, and a majority—including 98 percent in Indonesia and 92 percent in Sri Lanka—said religion is very important in their lives. In Singapore, while only 36 percent said religion was very important, 87 percent still said they believed in God or unseen beings, according to the Pew report.

This is further encapsulated in how religion is viewed as part of national identity. In Thailand, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka, more than 90 percent of Buddhist respondents say that “being Buddhist is important to being truly part of their nation.” In Cambodia, the percentage was 97 percent. This tracks with missionaries to those countries, who say their biggest struggle is combating ideas such as “to be Thai is to be Buddhist.”

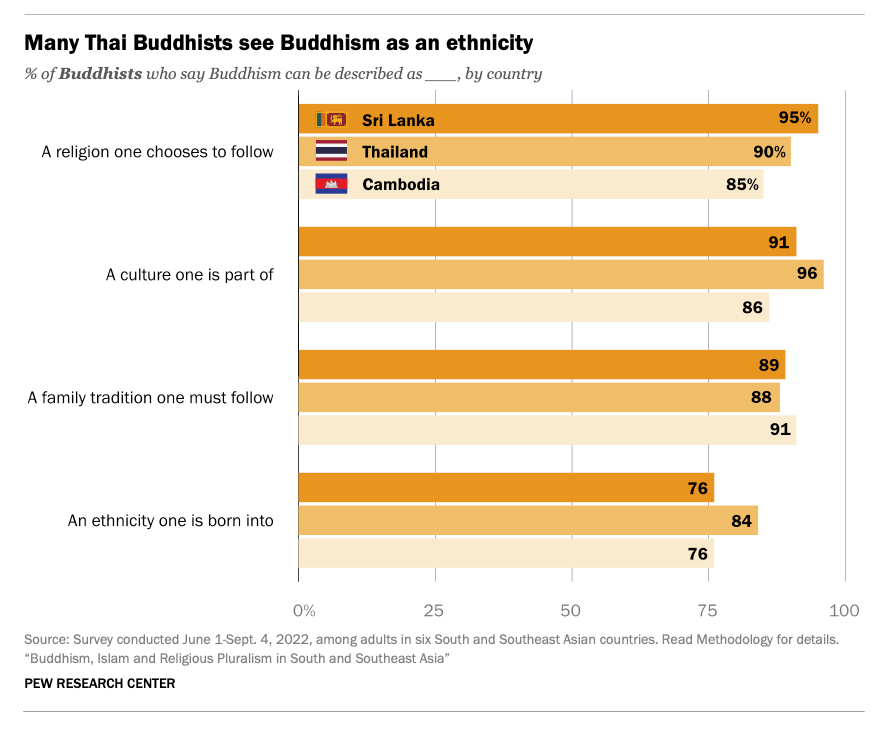

In addition, Buddhism is considered more than just a religion. “The vast majority of Buddhists in Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand not only describe Buddhism as ‘a religion one chooses to follow’ but also say Buddhism is ‘a culture one is part of’ and ‘a family tradition one must follow,’” stated the Pew researchers. Most Buddhists, including 84 percent of Thai Buddhists, also see Buddhism as “an ethnicity one is born into.”

In Cambodia, Sarah Ardu, a missionary who has served in the country for 25 years, observes the impact of the close tie between being Buddhist and being Cambodian. While young people are the easiest to attract to Christianity, when they grow up, “a large number of them revert to being ‘real Cambodians’ and uphold the normal Cambodian Buddhist way of life.” At the same time, the vast majority of Cambodians “will not be willing to give Jesus a try because of the cultural barrier of Westernized Christian religion.”

She believes that the way the gospel is being shared in Cambodia is not having a long-term impact on Cambodian Buddhists, because Western culture has become entangled with the gospel message.

“By making separation from their perception of Cambodian identity an essential part of following Jesus, we have sown the seeds of a gospel that is powerless to transform the deepest levels of life, family, and culture,” Ardu said.

Instead, missionaries need to turn from what is considered “correct Christian observance” to completely depend on Jesus and engage with Cambodian Buddhists at a heart level. Then, they can “stand in awe as the Holy Spirit brings [Cambodians] revelation and transformation without forcing conformity to Westernized Christian religion.”

Because religion and national identity are so closely linked, a majority of Buddhists in Cambodia, Sir Lanka, and Thailand also favor basing national law on Buddhist dharma, “a wide-ranging concept that includes the knowledge, doctrines, and practices stemming from Buddha’s teachings,” Pew noted. Yet the level of support varies: 96 percent of Cambodian Buddhists favor this, compared to 80 percent of Sri Lankan Buddhists and 56 percent of Thai Buddhists.

In Cambodia, the constitution states that Buddhism is the national religion and its government supports Buddhist schools. (Cambodia and Bhutan are the world’s only two countries to have Buddhism as their official religion.) In Sri Lanka, the constitution calls for its government to “protect and foster” Buddhism, giving it the “foremost place.” In Thailand, the constitution requires its government to “have measures and mechanisms to prevent Buddhism from being undermined in any form.”

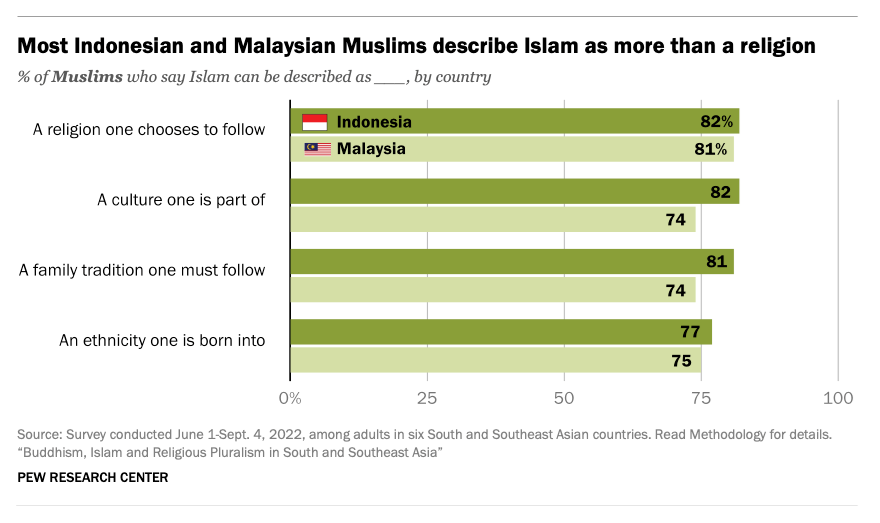

Meanwhile, Muslims in Southeast Asia similarly see Islam as intrinsically linked to their national identity. Nearly all adherents in Indonesia and Malaysia say being Muslim is important to being truly Indonesian or Malaysian, and three-quarters or more view Islam as a culture, a family tradition, or an ethnicity.

Islam is the official religion in Malaysia, and today the country practices a dual legal system of civil and sharia courts, with the latter only pertaining to Muslims and covering family and personal law. According to the Pew study, 86 percent of Malaysian Muslims support making sharia the basis of national law.

In Indonesia, where Islam is explicitly favored but is not the official religion, 64 percent of Indonesian Muslims say sharia should be used as the national law. Today Indonesia practices a “mild secularism,” according to Pew researchers, and its constitution states the archipelago is “based on the belief of the One and Only God.”

Hoon Chang Yau, a professor of anthropology at the Institute of Asian Studies at Universiti Brunei Darussalam, said Pew’s findings on Indonesia track with the conservative shift the country has undergone in the last two decades. “Due to the process of Islamization, Indonesian Islam no longer exhibits a ‘smiling’ or tolerant façade,” Hoon said. “This is concerning because such intolerance often translates into legislation, such as Sharia bylaws or regulations that limit the freedom and development of minority religions.”

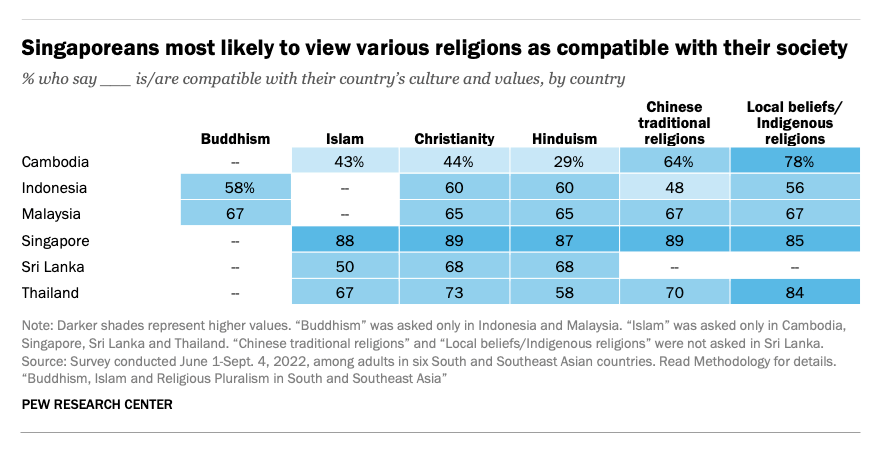

It also raises the question of whether minority religions, such as Christianity, are seen as compatible with each Asian nation’s culture and values.

Cambodians are the least likely to be pluralistic, with only 44 percent saying Christianity is compatible with their country’s culture and values. By comparison, 60 percent of Indonesians, 65 percent of Malaysians, 68 percent of Sri Lankans, 73 percent of Thais, and 89 percent of Singaporeans say Christianity is compatible with local culture and values.

Seree Lorgunpai, former general secretary of the Thailand Bible Society, is encouraged by the high percentage of Thais who feel that Christianity has a place within Thai society. He believes that for Christianity to grow in his country, Christians need to reach out to children and young people as it takes time to see the fruit. “To share the Good News, we should not only share the message, but we should show them what we teach.”

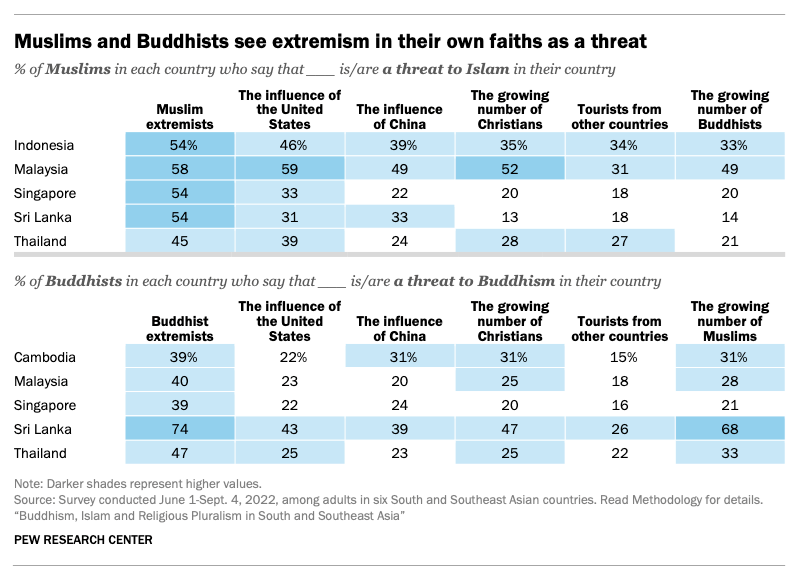

Conversely, many see the growth of Christians as a threat to Islam or Buddhism in their country, including 31 percent of Cambodian Buddhists, 35 percent of Indonesian Muslims, 47 percent of Sri Lankan Buddhists, and 52 percent of Malaysian Muslims. However, in each nation, a larger share of Muslims and Buddhists see extremism within their own faiths as a threat.

Singapore’s religious diversity

In Singapore, where no one faith makes up the majority, Pew found that 9 in 10 adults say Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Chinese traditional religions are all compatible with the city-state’s culture and values.

Based on the 2020 national census, 31 percent of Singaporeans identify as Buddhist, 20 percent claim no religion, 19 percent are Christians, 15 percent are Muslim, and the remaining 15 percent include Hindus, Sikhs, Taoists, and followers of Chinese traditional religions.

Christianity in Singapore has nearly doubled since 1980, while the religiously unaffiliated has also grown from 13 percent to 20 percent. Buddhism grew from 27 percent in 1980 to 42 percent in 2000 before dropping back down to 31 percent. Followers of Chinese traditional religion dropped from 30 percent in 1980 to 9 percent today.

Singapore’s “religious switching” also makes it unique. Only 64 percent of Singaporeans identify with the religion in which they were raised. In the other five countries surveyed, at least 95 percent of adults still identify with the religion in which they were raised. “Consequently, the share of people raised in each religion roughly matches the share who identify with that religion today,” Pew said.

In Singapore, while 32 percent of adults say they were raised Buddhist, only 26 percent identify as Buddhist today. Converting to another religion is also more welcomed among Singaporean Buddhists: Only 36 percent of the group believe it’s unacceptable to leave their religion for another. In comparison, 82 percent of Buddhists in Cambodia believe conversion is unacceptable, Pew found.

The percent of Singaporeans who identify as Christians today is 17 percent, while only 11 percent were raised Christian. The number of Singaporeans who say they are religiously unaffiliated today is 22 percent, while only 13 percent said they were raised with no religion.

A closer look at the data shows that these gaps between those raised in a religion and those who currently practice it don’t reveal the whole story, Pew noted. While 13 percent of adults raised Buddhist no longer identify with the religion, 7 percent of Singaporeans who were not raised in a Buddhist household now practice the religion. And while 9 percent of Singaporeans who were raised in a different religion or no religion now identify as Christian, 3 percent of people who were raised as Christians now identify with another religion.

Today only two-thirds of Buddhist parents in Singapore say they are raising their children in their faith (a quarter are raising them with no religion). In contrast, 90 percent of Christian parents in Singapore are raising their children in their faith. In other countries, “virtually all parents report that they are raising their children with a religious identity that matches their own,” stated Pew researchers.

Even though Singapore’s “nones” are an anomaly in the region, a majority still hold on to religious beliefs: 62 percent believe in God or unseen beings; 65 percent say they think karma exists; 43 percent say a person can feel the presence of a deceased family member; and 39 percent burn incense.

Roland Chia, the Chew Hock Hin Professor of Christian Doctrine at Trinity Theological College in Singapore, noted Pew’s findings that among religiously unaffiliated Singaporeans who feel personally connected to Christianity, 38 percent pray or offer respect to Jesus. It’s a sign that “disassociation with organized religion or religious institutions does not imply the full embrace of the secular mindset or worldview,” Chia said.

For Christians trying to reach this group, it’s important to try to understand their backgrounds and concerns, especially if they have left the church, he said. “However, the fact that many of those who identify as religiously unaffiliated are still pursuing some form of spirituality and nominally accept the core beliefs of Christianity—such as praying to Jesus Christ—serves as an important contact point for Christian witness,” Chia noted.

Overlapping religious practices

It’s not just the “nones” who are defying labels in their beliefs. Pew’s survey found that people of different religions believed in concepts or prayed to deities or founding figures of other religions.

For instance, three-quarters or more of adults in all six countries believe in karma, the idea that people will reap benefits for their good deeds and pay the price for bad deeds. That includes more than 60 percent of Christians in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka. Singapore’s Christians are the only religious group where less than half of adults (46%) believe in karma, Pew found.

Mathew Mathews, head of the Institute of Policy Studies’ Social Lab, found it surprising that so many Singaporean Christians would believe in karma, “especially when Christianity in Singapore is fairly conservative and many Christian churches are very hesitant to support syncretism of any kind.”

He added that some Christians may have understood karma as the concept of “you reap what you sow,” without the notion of reincarnation.

Compared to Christians in the other countries, Sri Lankan Christians are most likely to pray or offer respects (which could include burning incense, making food offerings, or making wishes) to a deity of another religion. The survey found that 61 percent of Sri Lanka’s Christians do so to Buddha, 58 percent to protector spirits or guardian deities, 41 percent to Allah, and 48 percent to the Hindu god Ganesh.

In contrast in Malaysia and Singapore, about 1 in 10 Christians pay respects to Guanyin, a Bodhisattva Buddhist believed to aid the suffering.

Ivor Poobalan, president of Colombo Theological Seminary in Sri Lanka, found this contrary to his own observations, noting that Christians in both traditional churches and younger denominations generally hold to a high view of Jesus’ unique claims as Lord and Savior.

“I find it well-nigh impossible to understand how the report could have arrived at the statistic that 61 percent of Christians worship the Buddha,” he said. “While much smaller numbers could reasonably be said to practice some form of syncretism due to marriage or other social pressures, the vast majority are marked by a strong sense of religious identity, which includes an exclusive allegiance or devotion to the Christian/Catholic faith.”

He believes the Pew’s finding that 71 percent of Muslims worship or pay respect to Buddha even more unlikely.

The Pew report also found that a majority of Sri Lanka’s Christians have an altar or shrine in their home and burn incense. A little less than half of the country’s Christians say they practice meditation, which is higher than Christians in other countries.

The survey also found that among Christians, about half of the believers in Indonesia, Singapore, and Sri Lanka believe Christianity is the only true religion, while only 37 percent of Malaysians agree with that statement.

Christians in these countries were split on whether a person could be a Christian and celebrate the Buddhist festival of Vesak or the Muslim festival of Eid. Most Christians in Indonesia (63%) and a third in Malaysia (35%) said a person cannot be a Christian if they celebrate Eid, while half of Christians in Singapore (50%) and a large number in Sri Lanka (38%) said the same about Vesak.

Across all religions, majorities agreed that a person could not be a member of their religion if they disrespect their elders or their countries.

On the topic of drinking alcohol, the region’s Christians were much more split. While 74 percent of Christians in Indonesia see drinking as disqualification from Christianity, the number drops to 62 percent in Malaysia, 60 percent in Sri Lanka, and only 18 percent in Singapore.

Religion-state integrationists less willing to accept Christian neighbors

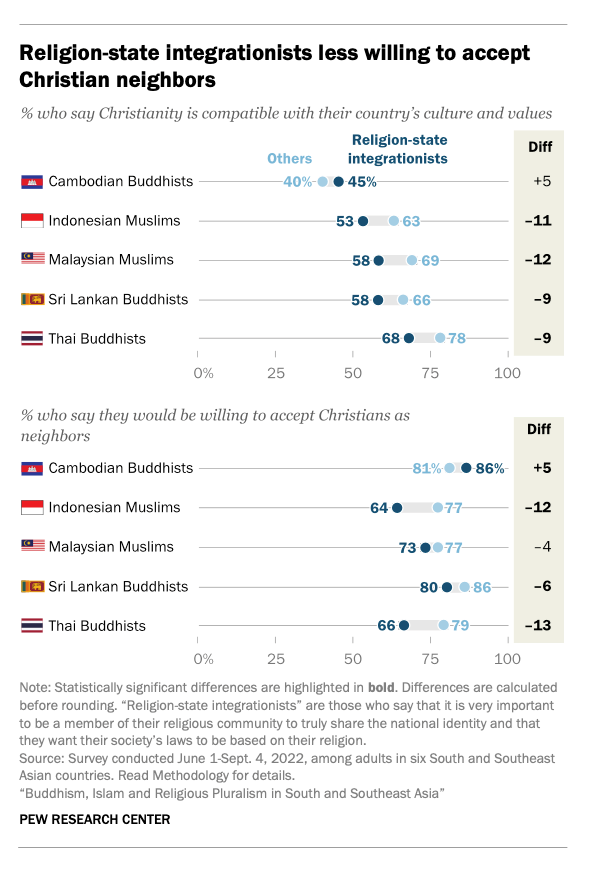

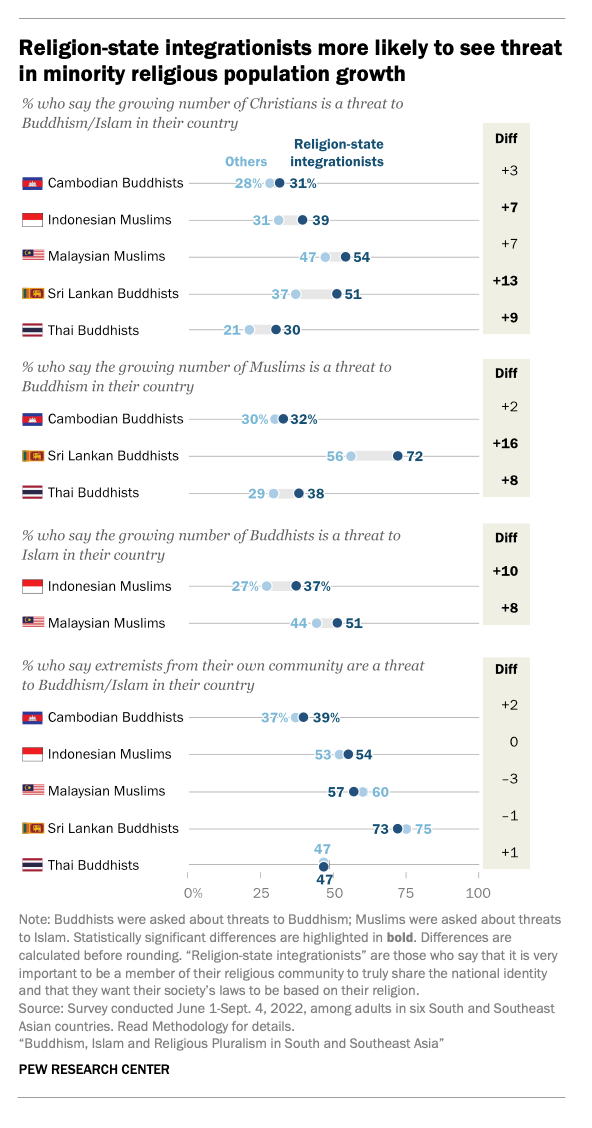

In the surveyed countries with Buddhist or Muslim majorities, people who say it is very important to be a member of their religious group to truly share their national identity and want their country’s laws to be based on their religion were categorized by Pew as “religion-state integrationists.” They are more likely to support religious leaders becoming politicians, think religious leaders should talk about the politicians they support, and believe that if a person does not respect their country, they can’t be part of the religion.

“A majority of Muslims in Indonesia (57%) and Malaysia (69%) are religion-state integrationists, as are most Buddhists in Sri Lanka (72%) and Cambodia (75%),” the report noted. “A sizable minority of Thai Buddhists (45%) also fall into this category.”

Poobalan said the high percentage of Sri Lankan Buddhists who fall into this category is concerning. “It is this mentality that made post-independence Sri Lanka inhospitable to religious and ethnic minorities and created tensions and the likelihood of conflict between religious communities,” he noted.

Religion-state integrationists are also less likely to accept Christian neighbors. The Indonesian Muslims who fall in that category are less likely to say Christianity is compatible with Indonesian culture and values (53% versus 63%). They are also less willing to accept Christian neighbors (64% versus 77%).

“Buddhist nationalism has been linked with antagonism and violence between Buddhists and religious minorities in countries dominated by Theravada Buddhism, including during the Sri Lankan civil war,” stated Pew researchers. “Similarly, some scholars have asserted that there is a connection between rising ‘religious nationalism’ and xenophobia in Muslim-majority Indonesia.”

Religion-state integrationists are also more likely to see the growth of Christianity in their country as a threat to the majority religion. Most significantly, Sri Lankan Buddhists who fall under the term are more likely to view Christian growth as a threat compared to other local Buddhists (51% versus 37%). However, Sri Lankan Buddhists are more inclined to see Muslim growth as a threat to Buddhism in their nation.

Among Buddhists in Cambodia and Thailand, only 57 percent and 58 percent, respectively, believe Christians are very/somewhat peaceful. Still, majorities in every country said they were willing to accept members of other religions as their neighbors.

In general, the survey found that a majority of Malaysians (62%), Sri Lankans (62%), and Singaporeans (56%) believe having people of different religions, ethnic groups, and cultures makes their country a better place. Half of Indonesians agree with this statement, while 41 percent believe it makes no difference. A majority of Cambodians (54%) and Thais (68%) also agree that it doesn’t make a difference.

Poobalan finds hope in the percentage of Sri Lankan adults who value diversity. “Such a sentiment provides encouragement that, free from the influence of political opportunists, average Sri Lankans greatly appreciate society’s pluralistic nature,” he said. “This shouldn’t be surprising since the country has a recorded history of 2,500 years that stands out for its religious and cultural pluralism and peaceful co-existence of traditions.”

Over in Indonesia, Hoon believes that the diverse environment provides opportunities for Christians to engage in interfaith dialogue and build bridges, while at the same time, they need to assert their constitutional rights to religious freedom. “Everyday life in the neighborhood still involves cross-cultural interactions,” Hoon said. “Therefore it is imperative for Christians to continue fostering such spaces, extending friendship and hospitality to non-Christians to promote goodwill and understanding. This way, during times of social tension, their neighbors will stand up for them.”

Pew’s other interesting findings about Christians in the six countries include:

- Nearly all Indonesian Christians, 93 percent of Sri Lankan Christians, and 78 percent of Malaysian Christians say religion is very important in their lives. Among Singapore’s Christians, that number drops to 61 percent.

- In Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia, 74 percent or more of Christians believe Christianity is an ethnicity one is born into. In comparison, only 41 percent of Singaporean Christians believe that.

- While 50 percent of Singaporean Christians see Christianity as a family tradition one must follow, that number is much higher among Christians in Malaysia (74%), Sri Lanka (88%), and Indonesia (92%).

- Nearly half of Christians in all six countries think that spells, curses, or other magic influence people’s lives.

- In Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia, 80 percent or more of Christians believe in a Judgment Day, compared to only 48 percent in Sri Lanka.

- While a majority of Christians in Indonesia and Malaysia think religious leaders should talk publicly about the politicians or political parties they support, only a quarter of Christians in Singapore and Sri Lanka agree.

- While most Christians in Indonesia (83%), Sri Lanka (67%), and Malaysia (61%) believe it is “unacceptable” to leave Christianity for another religion, many also believe it is unacceptable to “try to persuade others to join” Christianity—including 72 percent in Indonesia, 75 percent in Malaysia, and 87 percent in Sri Lanka. In Singapore, only about 4 in 10 Christians say either leaving Christianity (42%) or persuading others to become Christians (39%) is unacceptable.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month