For decades, we’ve thought of women as more religious than men.

Survey results, conventional wisdom, and anecdotal glimpses across our own congregations have shown us how women care more about their faith, though researchers haven’t been able to fully untangle the underlying causes for the gender gap across religious traditions and across the globe.

Now, recent data shows the long-held trend may finally be flipping: In the United States, young women are less likely to identify with religion than young men.

The findings could have a profound impact on the future of the American church.

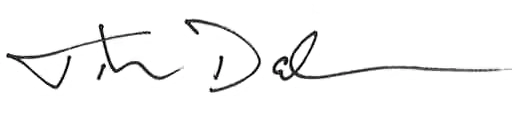

As recently as last year, the religion gender gap has persisted among older Americans. Survey data from October 2021 found that among those born in 1950, about a quarter of men identified as atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular, compared to just 20 percent of women of the same age. That same five-point gap is evident among those born in 1960 and 1970 as well.

For millennials and Generation Z, it’s a different story. Among those born in 1980, the gap begins to narrow to about two percentage points. By 1990, the gap disappears, and with those born in 2000 or later, women are clearly more likely to be nones than men.

Among 18- to 25-year-olds, 49 percent of women are nones, compared to just 46 percent of men.

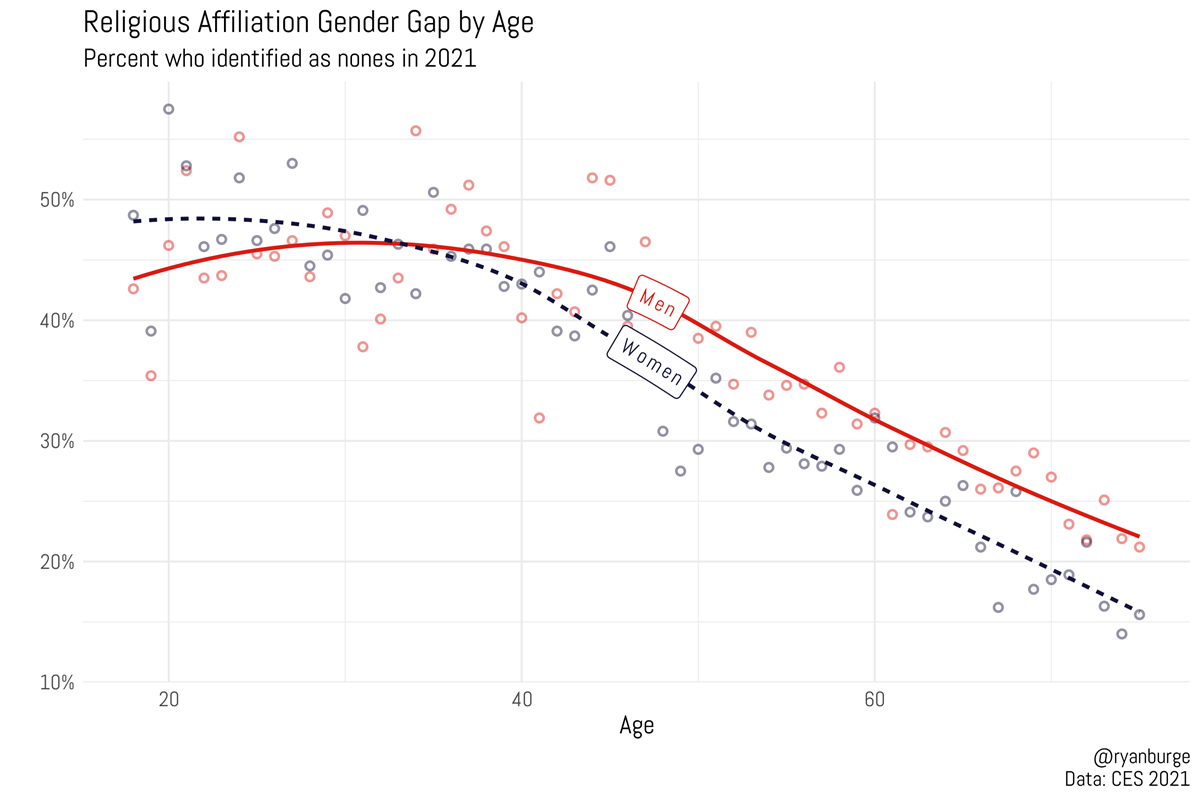

There’s also a gender gap in church attendance. This pattern has been so stark that Pew Research Center found in 2016 that Christian women around the world are on average 7 percentage points more likely than men to attend services; there are no countries where men are significantly more likely than to be religiously affiliated than women.

In the US, older men are more likely to say they never attend church services when compared to women of the same age. Among 60-year-old men, 35 percent report never attending; it’s 31 percent of women.

While the difference between men and women identifying as nones doesn’t disappear until those born in the 1990s (today’s 30-year-olds), we see the gender gap in church attendance has closed for earlier generations as well. For people born as early as 1973 (in their late 40s today), men and women are equally likely to say they never go to church. The youngest adults are less likely to report never attending services compared to those who are between 35 and 45 years old.

What demographic factors may be leading to this emerging gender difference in the religiosity of young men and women?

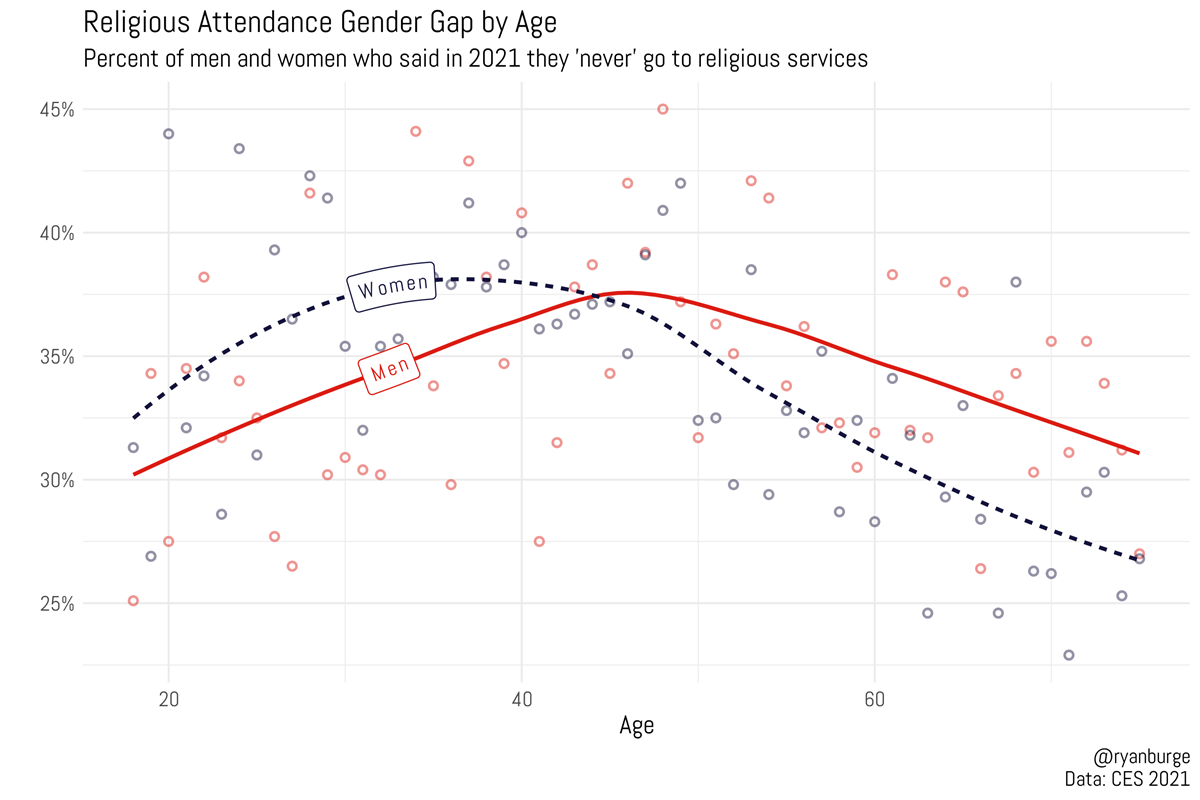

There’s no real difference in the share of male and female nones among Black, Asian, and other racial groups. But among Hispanic young people, men are 8 percentage points more likely to be nones than women.

Among white respondents, women are 9 percentage points more likely to say that they have no religious affiliation compared to white men.The gap among Gen Z white people is a large part of the story since white respondents make up half of 18- to 25-year-olds.

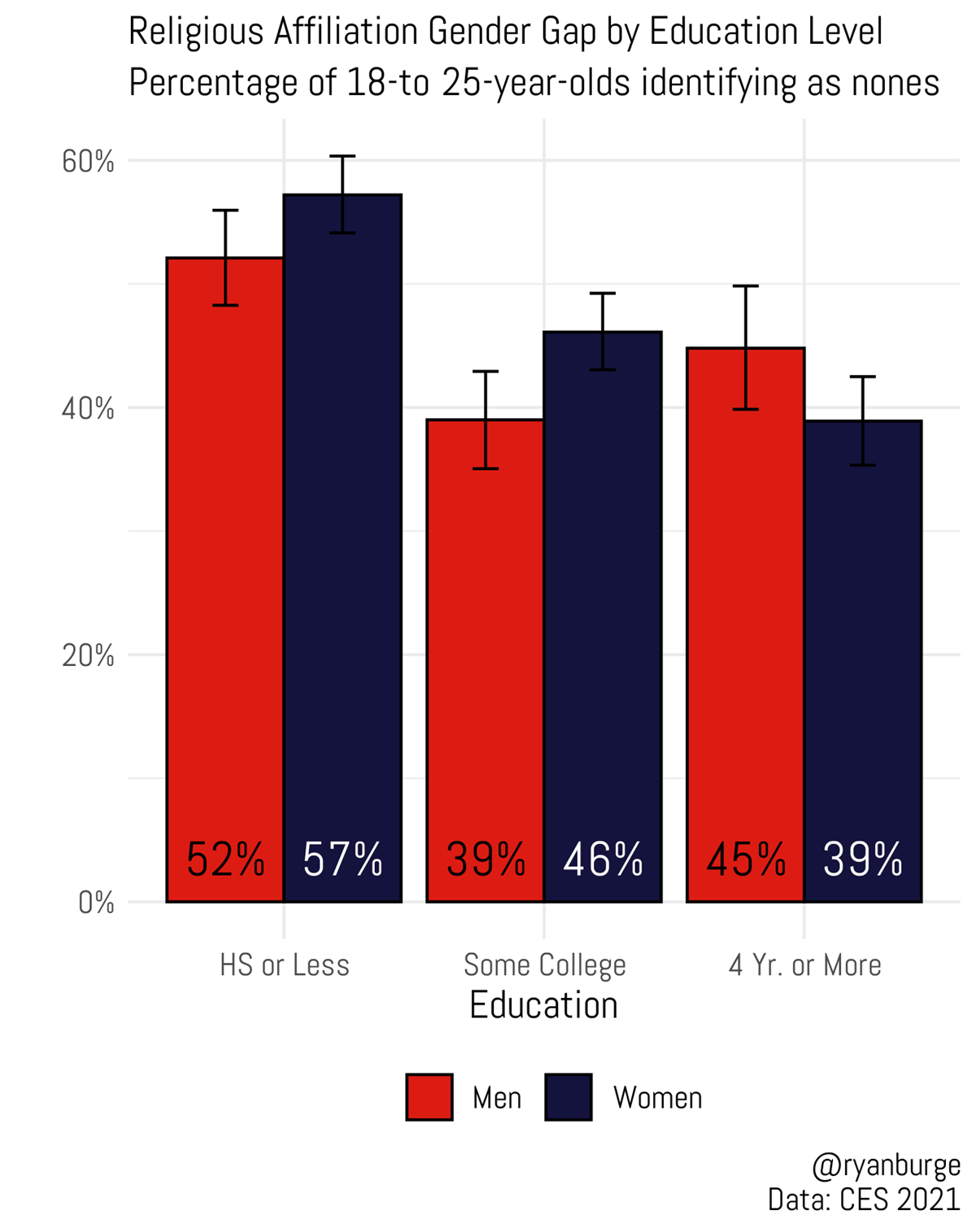

Education may be another significant factor. Among college-educated adults under 25, women are slightly less likely to say they have no religious affiliation compared to men (39% of women versus 45% of men).

However, among those who have not completed a four-year degree but are working toward one, there’s a clear difference. Fifty-seven percent of Gen Z women with high school diplomas are nones, compared to only 52 percent of men. Among those who have taken some college courses but have not completed a bachelor’s degree, there’s a seven-point gap between men and women.

Christians have noticed the longstanding age gap over the years and tried to address it. Men’s ministries focused on male discipleship and bringing husbands and fathers back into the fold, but women continued to outnumber men in evangelical churches by a 10 percentage-point margin.

Some major voices influencing evangelical Christianity had specifically called out young men for their lack of responsibility and religious devotion. Mark Driscoll preached about biblical manhood, Owen Strachan said that “manhood is doing hard things for God’s glory and the good of others,” and Jordan Peterson’s rise to fame is based largely on his insistence on a “gospel of masculinity.”

These voices and other efforts to keep young men in the fold could have affected male church involvement in recent years—but they may have been a factor in deterring women’s attendance too. As one recent CT book review notes:

Evangelical women have long attended church at higher rates than evangelical men. But today that gap is narrowing, not because more men are coming but because more women are leaving. Such women are increasingly likely to “deconstruct” their faith or identify as “nones”—a rising population of the religiously disaffiliated.

As Lyman Stone wrote two years ago, “Making your church manlier won’t make it bigger.” It could be a factor in making it smaller.

The drop in attendance and affiliation by young women leaves the future of the American church in a precarious position. For pastors of older congregations, it’s not uncommon to look out at the people on Sunday and see women outnumber men by factors of two or three. If this trend continues and Gen Z women do not return to church as they move into midlife, it could spell a real crisis for congregations who rely on the leadership and service supplied by that vital part of the church community.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month